By the early 1920s, Seattle resident Carlia S. Westcott had become the first woman granted a license to work as a marine engineer in the United States. (Marine engineers design, operate, repair and/or maintain machinery and equipment on ships; quite a few of those engineers perform similar work on offshore installations.) The significance of Westcott’s achievement was highlighted by H.C. Lord, U.S. inspector of boilers, at the time she was formally awarded her first-of-a-kind license. “You are showing the way for all the other women of the country,” proclaimed Lord on that occasion.

A pivotal episode in Westcott’s decision to become a marine engineer had taken place a year earlier, when she joined her husband – described in Woman Citizen magazine as “a veteran towboat man” – on one of the tugboats of the Cary-Dan’s Towing Company operating in the Seattle region. Mr. Westcott served as the company’s chief engineer and Carlia was on board a vessel for an extended period of time to assist him there and carry out the tasks of a fireman. The responsibilities for such a position in a maritime environment typically include performing minor maintenance and repairs as needed to engineering equipment.

“Men on the fleet thought this work would be so strenuous that Mrs. Westcott would want to land at the end of a few weeks,” recounted Woman Citizen, “but that wasn’t the stuff she was made of.” This article further reported, “She stuck to her job and earned the approval of her husband, who said he never had a more conscientious hard-working fireman.”

That experience out at sea strengthened Westcott’s resolve to pursue a marine engineering career even if there were not any women in that profession in the United States at the time. When discussing why women were especially well-suited for such a career, Westcott asserted that “the principal requirement is close attention to duty.”

As a first step towards certification, Westcott took and passed the tests of the Marine Engineers’ Beneficial Association, No. 38, in Seattle. She then took the U.S. Steamboat Service examination. To say that she passed with flying colors would be an understatement. “Her showing in the examination was as near perfect as it could be,” confirmed the supervising inspector. “She is a capable young woman of the type of which America should be proud.”

This license allowed Westcott to serve as chief engineer for vessels weighing up to 75 tons (68 metric tons) and an assistant engineer for vessels weighting up to 300 tons (272.2 metric tons) for voyages as far as Alaska and on lakes, bays, sounds, and all adjacent inland waters.

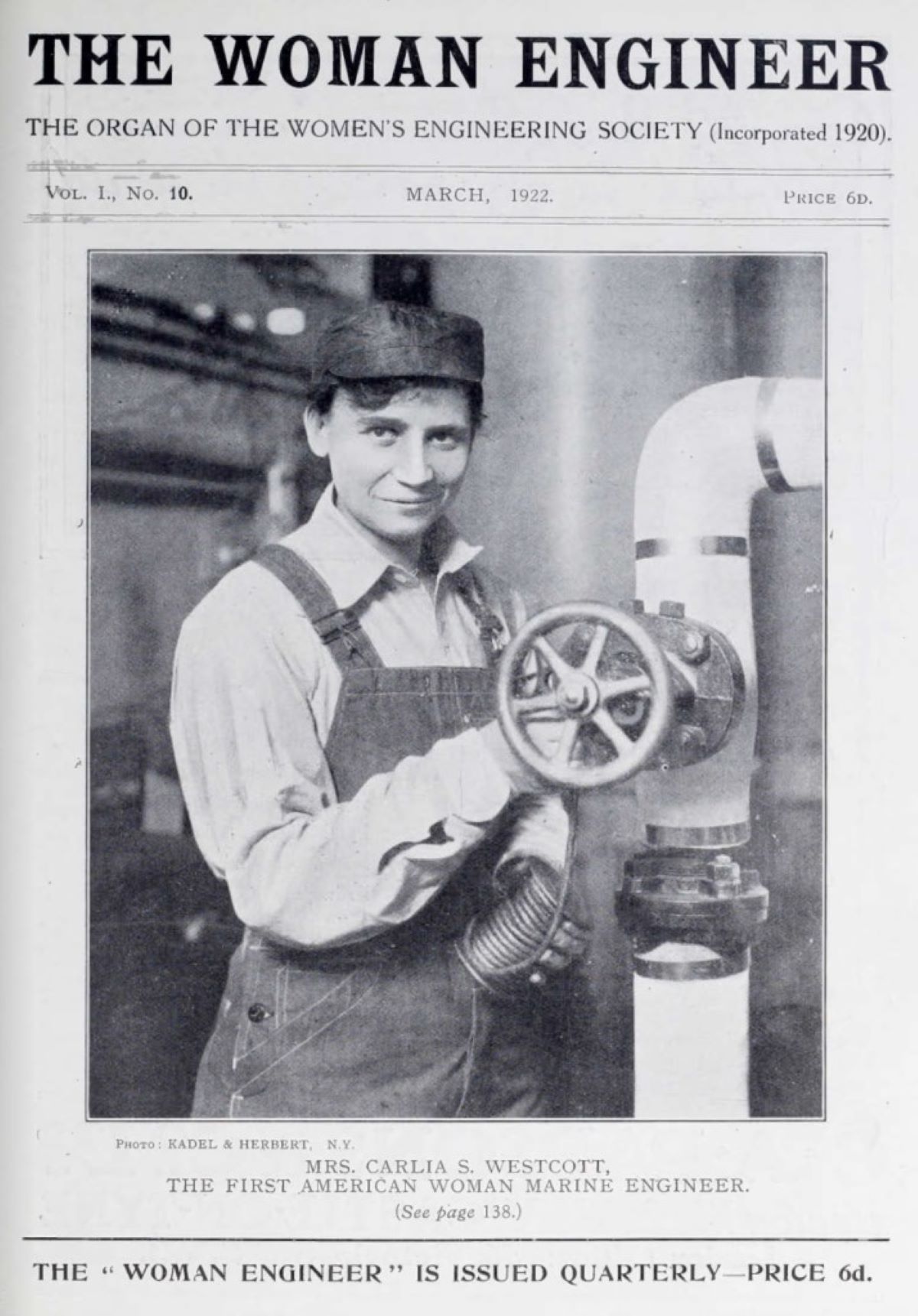

News of Westcott’s trailblazing accomplishment was eventually reported throughout the United States and beyond. The accompanying photo of Westcott, which shows her working on board a tugboat and specifically packing the stuffing box of a valve inside a steam feed pipe, was likewise widely disseminated.

In May 1922, the overall impact of Westcott’s then-unique career choice was highlighted in the New York Times. This newspaper noted, “With the advent of the woman engineer and the publicity given to the entrance of Mrs. Carlia S. Westcott into the field of marine engineering, a great increase of interest is being shown in different countries in the part that women will probably play in engineering in the future.”

In January of that same year, Power magazine had offered a similar perspective on Westcott’s potential long-term legacy for women. This article started off by stating, “’Alice, you had better get a fire started under No. 3.’ ‘Mabel, that pump is giving trouble again, you had better tear it down and see what’s wrong.’ ‘Genevieve, see you can fix that lubricator.’” The magazine then asserted, “It sounds funny today, but who knows what the future will bring?”

Image Credit: Public Domain

For more information on Carlia S. Westcott, please check out https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carlia_S._Westcott

Leave a comment