Henry Brown was born into slavery in 1815 on a plantation in Virginia’s Louisa County. At the age of 15, he was sent to the state’s capital city of Richmond to work in a tobacco factory there. He resided in Richmond with his wife Nancy and their three children, all of whom were likewise enslaved. In a heartbreaking and unexpected turn of events, the master of Brown’s wife and children ended up selling all four of them to a slave owner in North Carolina. (Nancy was expecting another child at the time.) With his family no longer with him, Brown eventually resolved to escape to freedom in the North.

Brown was helped in that daring effort by James C.A. Smith, a free black man, and a white shoemaker named Samuel A. Smith. With the support of both of those men (who were not related to each other), Brown came up with a plan to have himself delivered by the shipping company Adams Express to a free state.

As a key part of this plan, Samuel A. Smith traveled to Philadelphia and met there with members of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society about how to best accomplish the shipment of Brown to the North. It was agreed to have the wooden crate containing Brown transported via Adams Express to the Philadelphia office of Passmore Williamson, a Quaker merchant who was active in the abolitionist organization known as the Vigilant Association of Philadelphia (also called the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee).

To get out of work on the day on which he was set to begin his escape, Brown deliberately burned one of his hands with sulfuric acid. He subsequently made his way into a crate that was 3 by 2.7 by 2 feet (0.9 by 0.8 by 0.6 meters). This crate, which prominently featured the phrase “dry goods,” had a single hole cut into it for air and was lined with woolen cloth. Brown — armed with some water and just a few biscuits for sustenance — embarked on his audacious trip out of slavery on March 29, 1849.

Over the next 27 hours, Brown remained in the crate and was ultimately transported by delivery wagon, train, steamboat, delivery wagon again, train, ferry, train once more, and delivery wagon a final time. Along with the ever-present risk that he might be discovered and captured at any point in the journey, Brown had to deal with various indignities and potential injuries. Despite being labeled with “handle with care” and “this side up” instructions, for example, the crate was handled roughly and even placed upside down several times.

When the crate arrived at its destination on March 29, Brown was greeted by not only Williamson but also a few other members of the Vigilant Association of Philadelphia. Those other members included black abolitionist and Underground Railroad conductor William Still and the staunch anti-slavery Presbyterian minister James Miller McKim. “How do you do, gentlemen?” Brown reportedly said as he finally emerged from the crate after being inside it for more than a day. A religious man, Brown subsequently celebrated his newfound freedom by performing a song based on Psalm 40 from the Bible.

In one of the autobiographies that he would write, Brown made it abundantly clear that his multimodal escape from Richmond to Philadelphia was very much worth the uncertainties and possible dangers it involved. Brown asserted, “if you have never been deprived of your liberty, as I was, you cannot realize the power of that hope of freedom, which was to me indeed, an anchor to the soul both sure and steadfast.”

Brown went on to become a renowned abolitionist speaker in the North. Only about three months after his journey inside a crate, Brown was good-naturedly nicknamed “Box” while attending an anti-slavery convention in Boston. From that point forward, he went by the name Henry Box Brown. Starting in the early 1850s, Brown settled in England and remained there until returning to the United States in 1875. In 1886, he moved to Canada. Brown died in Toronto on June 15, 1897.

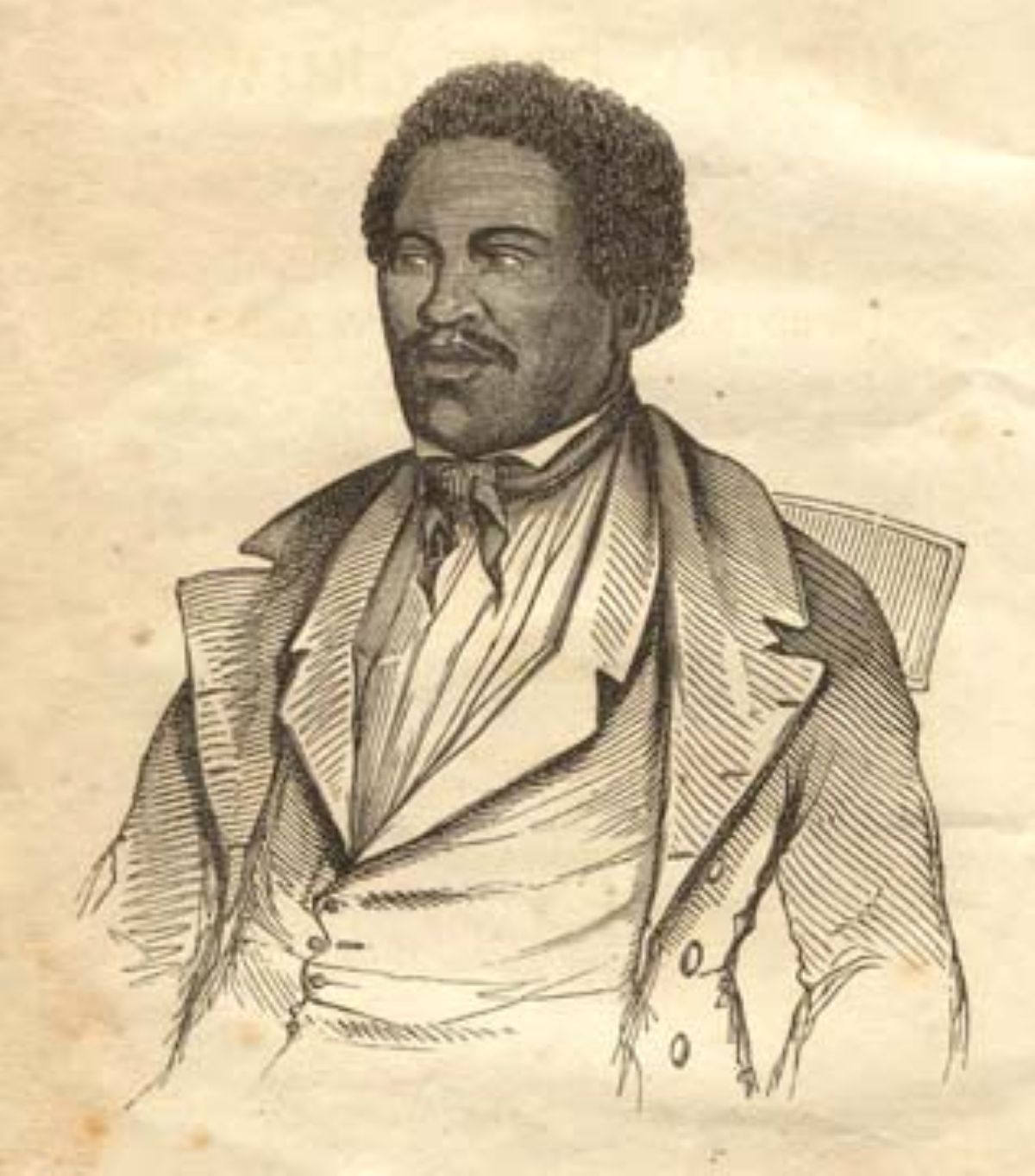

Brown’s legacy is commemorated with a monument along the Canal Walk in downtown Richmond. This monument is a metal reproduction of the crate used by Brown for his escape. In addition, a historical marker honoring Brown was installed in Louisa County in 2012. (The accompanying image of Brown was created in 1849.)

Image Credit: Public Domain

For more information on Henry Box Brown, please check out https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Box_Brown

Leave a comment